This post is not about whether austerity works as an economic policy, nor is it about the governments’ commitments to the disadvantaged (this isn’t the apocryphal austerity blog I was writing that I may have told some of you about – that got really long). This is primarily a response to many friends that, although they think austerity doesn’t work, and that our commitments to the disadvantaged are more important, still are very worried about deficit. I’m not saying here that we should just ignore deficit, more just that there is a lot of theory and evidence out there to suggest that deficit is not nearly as bad as politicians would have us believe.

Basically when we all worry about deficit, we worry that we are spending more money than we are earning, like in the same way we would worry if it was our bank account. But it’s not quite like that.

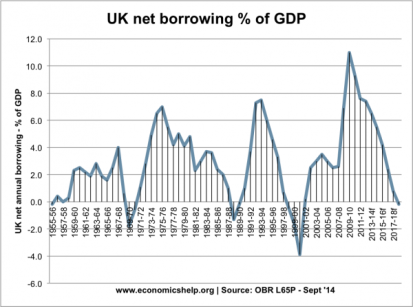

Firstly – as some of you may know from Cameron’s blunder back in 2013 – there’s a difference between deficit and debt. The deficit is how much more the government is spending than it’s taking in revenue (that revenue being mostly taxes), whereas the debt is how much overall debt we’ve accumulated. Deficit fear mongers tend to stress the former whilst Krugman and his Keyensians emphasise the difference between our debt and our GDP (how much stuff we have and how well our economy is producing). The reason for this is that the deficit has been slowly zig-zagging upwards since the 50’s (please note the last few years on the graph are projections),

(1)

(1)

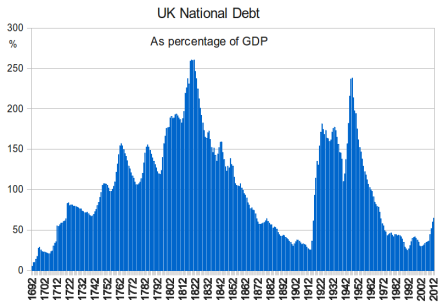

whilst the debt to GDP ratio is historically speaking not too bad (you can’t see it that clearly on this graph but we are currently loitering around the 100% mark).

(2)

(2)

Admittedly that post-war debt wasn’t paid off until 2006, which is not ideal but interest payments were always manageable.

Internationally there is also other countries with higher debt to GDP ratios: Japan is currently at 255%; and a handful of other European countries are also slightly above us (Follow the link for a great interactive map put together by the economist 3). Perhaps something that speaks louder is the fact that Germany – that economic powerhouse, eurobully – is at 80% to our 100%. So to stretch the personal bank account analogy, it’s like we are spending more than we’re earning, but we’ve been having a bad time recently and we’ve got some breathing space in our overdraft.

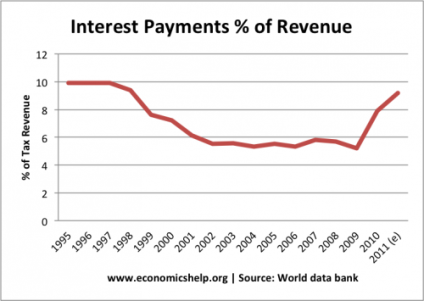

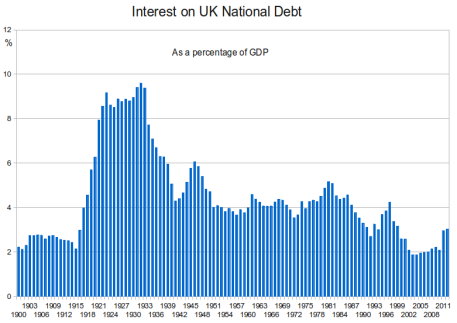

But which makes more sense to look at: spending to revenue (deficit); or debt to GDP? I will come back to spending and debt later, but first I want to pick up on the point made by Jeffrey Dorfmann that although high GDP increases potential for tax revenue, it doesn’t necessarily generate high revenue, and given it’s your revenue (how much you’re taking in) and not your GDP (how much your stuff and activity is worth) that’s going to pay that debt, this is an important difference to consider (4). I won’t bore you by pointing out how many of Dorfmann’s arguments are awful – and please don’t take the rest of his article seriously – but I will say I think he’s right – it does make more sense to look at revenue than GDP (although GDP may be a better when thinking about employment). If we take a look at the actual way that the countries get reshuffled on the screwed-to-okay list detailed in the Dorfmann article – the salient points are still pretty similar: no one is denying that the US and UK have pretty large debts internationally speaking, but Dorfmann’s picture of crippling debt payments ignores the ultimate truth that we’re really not paying too much interest on that debt.

(5)

(5)

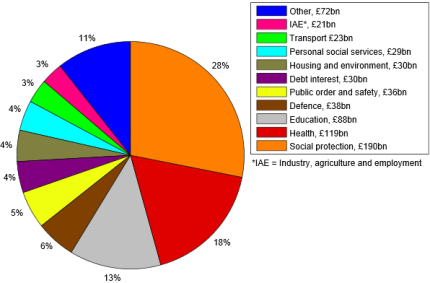

This graph only goes up to 2010, but you can see from the pie chart below that Interest payments are currently about 4% of the national budget,

(2)

(2)

which if it was my bank account I’d probably want to reign it in a bit if I’m honest, but half of my income goes on my rent, and I am generally financially risk averse in a way that would never be advisable for national economy (or a person for that matter), all of which illustrates how the household analogy doesn’t really work.

Further Disanalogies Between National and Personal Debt

The other important thing to understand is that unlike me and my back account, the government don’t have to wait until payday before they start spending money. When the government spend money they create it, the money essentially appears in the accounts of wherever they’re spending it; conversely when people pay taxes it doesn’t go anywhere, it just disappears from their accounts. If the UK really wanted to get rid of its debts they could just create more money, as is attested by many economists (6) going back to Paul Samuelson and including Paul Krugman (7), and even Alan Greenspan (8). So when people say, ‘the money’s got to come from somewhere’ the truth is it doesn’t really (this is, I believe, what the band Queen really meant when they wrote ‘It’s a kind of magic’…ignoring all the other lyrics). But what about Greece? What happened there? This is just the point – Greece can’t print their own money and the European banks were either too slow, or unwilling to bail them out in time.

The difference (the debt) is funded mainly by bonds, that is, the government gives people little golden IOU’s with promises to pay them back with interest – which they have never failed to do. And nor could they as discussed.

It gave me brain-ache thinking ‘surely they can’t just make the numbers up as and when they please?’ Well in a sense the government can, but once that money is out in the world it is real: money is a means of equating and mobilising value – values of things, people’s time and services – if you put too much out there, then you just raise the number that things are held to be equivalent at – that is, it causes inflation.

This is where another very salient contingent fact comes in: inflation rates are so low that earlier this year they even actually fell below zero (9). This is not great for the economy, which is why Japan have desperately been trying to create inflation (10), but the point here is that worries about creating inflation by generating money are just not relevant.

So why would governments want us to believe there is such a problem? There are many answers to that and I’ll let you make up your own, but my feeling is it’s a mixture of ignorance and scare mongering. This video – although a bit cringey – gives a really good impression of that, and surmises quite a lot of what I’m saying in the latter half of this post (11). For the more economically educated of you there are a bunch more confusing arguments on how we are not crippling our kids in this article (12).

Dear Vegetative State, why would anyone want to create inflation (i.e. Japan)? I don’t understand – please enlighten me. Sincerely, Lost In Economics

LikeLike

Hello Katrina,

Sorry for the slow reply. Breaking into the language and principles of economics is time consuming because there is a lot of jargon and a lot of principles, some of which often cancel each other out – it interests me the parallels with the environment here – but taken separately the principles are often surprisingly simple. A website I have found consistently helpful is this one: http://www.economicshelp.org/ designed to help A level students. It’s simple and more importantly one of the few resources on economics that is neutral.

Basically, inflation stops people from hoarding money: if you know things are slowly going to get more expensive then you know that it’s no good to have your money lying around slowly decreasing in value.

On the converse side, inflation also makes it a bit easier for debtors: If you are £500 in debt, that £500 will be less valuable down the line in an inflating economy, whereas any assets you have or income will continue to grow with the economy. This in turn encourages borrowing and lending which is good for the economy.

Most economies try to aim for an inflation rate of about 2-3%, so it’s quite modest and is really just designed to stop things from stagnating.

This article, explaining in a bit more detail, is relatively clear: http://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/111414/how-can-inflation-be-good-economy.asp although as I say, jargon in economics is a bit like trying to untie a ball string.

Apologies for the bizarrely patronising and officious tone of this message, I have been watching too many web-tutorials recently.

LikeLike

It is pretty important to balance the books. Yes, you can borrow money in times of crisis, but how far do we let this go? Our national debt is huge (and I don’t want comparisons to WWII or the Napoleonic Wars as they are irrelevant), and getting bigger, despite the so-called “savage” cuts of the last administrations.

Yes, you should run the economy like a business or like your household budget. It’s simply a rather large business/household with a budget that needs to be allocated for certain services. The key is to balance the books and prioritise areas in which you think more money should be spent. That’s what I was taught in economics classes at college and I have no reason to doubt my professors.

Never was it suggested that you should constantly spend more than you’re bringing in (which the UK has been doing for a decade or so now). Why act like the national debt (which is still growing btw) is no big deal? Maybe because we don’t have to pay for it? Our grandchildren will. Even economists like Keynes (who did THE worst deal with the USA at the end of WWII which we only paid off in 2005/06) would not have advocated the nonsense being suggested by some. Our economy is doing OK, unemployment at its lowest for 40+ years and so it’s not really a time for huge govt. spending. That time was probably in 2008/09.

LikeLike

Hello Mark, thanks for your comments. Just to clarify, the post is about how much we should worry about the debt we currently have – I’m not arguing that we shouldn’t ever worry about debt. Nor am I arguing that we should consistently spend more than we are bringing in, the point is that we’re not paying a large percentage of our budget on our debts. So if we’re not struggling to make repayments, and realistically nor will our grandchildren be, is there really such a problem?

More controversially – and this is not an argument I make in the post – you may even think that it’s better to spend now rather than later. Any sensible business reinvests everything it makes, and since spending is cheaper now and creates growth sooner, it’s not implausible to think that what is accumulated from that growth will outstrip what we are paying back in debt. And so it’s also not implausible to think that spending more than we earn may even be in fact the most sensible economic policy. For example I have a huge student loan, but repayments are so low that it just doesn’t make financial sense to try to pay it off, it makes more sense to use my money to earn more money, if I had the opportunity to take a similar loan to fund my PhD, I would jump at the chance. But I don’t have any real position on this, my only point is that we needn’t act so deliriously worried about debt.

All of the sources I have referred to in my blog have also had a considerable education in economics. If there is something that you’ve learnt from your professors that can illuminate why my arguments are wrong footed I’d be interested to hear it.

Finally your point about Keynes. As I’ve already said I don’t consider myself a Keynesian, nor do I think of myself as a Krugmanite (I actually don’t think that Krugman’s views are as close to Keynes’s as he pretends), but I do admire Keynes as a human being. I don’t know enough about the situation to know whether if someone else had – or indeed would have – taken on such a difficult role things would have been much better. What I do know is that Britain was bankrupt and had very little to barter with, we also still owed America huge sums from the first world war. I also know that Keynes was in extremely ill health during the negotiations and even suffered a heart attack during them, it seems odd that he would be chosen to do it if there wasn’t someone better suited. All things considered it seems unfair to blame the deal on one man.

LikeLike